Frank Finnigan is not in the Hall of Fame, nor was he ever the biggest star for the original Ottawa Senators. From 1923 to 1937, he only led his team twice in scoring and was overshadowed by future Hall-of-Famers Cy Denneny, Alex Connell, Frank ‘King’ Clancy and Frank Nighbor. Yet, Finnigan’s No. 8 hangs from the rafters beside Daniel Alfredsson’s No. 11 at the Canadian Tire Center. Much of that has to do with his role in bringing the Senators back to Ottawa in 1992.

Joining the Ottawa Senators

Finnigan was born in Shawville, Quebec in 1901 and, from a young age, he showed he was a talented hockey player. In 1921, he joined the University of Ottawa’s senior hockey team, but not as a student. He had just started grade nine and was paid to play for the team and thus, was not required to hand in assignments. However, because he still lived in Shawville at the time, he was given the nickname, ‘The Shawville Express,’ as he had to take the train to Ottawa for games.

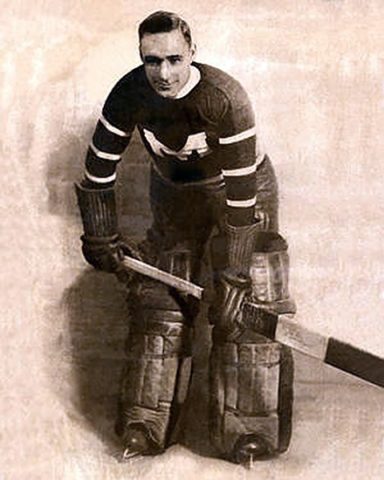

He joined the Senators in 1923-24. One of the greatest teams of the era, they won back-to-back Stanley Cups in 1919-20 and 1920-21, plus another in 1922-23. It was the NHL’s first dynasty, and the majority of the players on those rosters were inducted into the Hall of Fame. To join such a team was an incredible honor for a 20-year-old, and although he only played four games and scored no points, Finnigan was part of something greater.

The following season, he became a regular on the Senators, playing 29 games, missing only one match. However, he had big shoes to fill – before the season, long-time star Punch Broadbent, along with goalie Clint Benedict, were sold to the Montreal Maroons. Broadbent had been with the team since 1912 and was consistently one of the Senators’ top scorers and toughest forwards. In the 1921-22 season, he scored one or more goals in 16 straight games, an NHL record that still stands. He might have been the highest-scoring Senator of all time if he hadn’t left to serve in World War I.

Finnigan did his best to make Broadbent’s absence hardly noticable, but on a team that included Denneny, Nighbor, George Boucher and Clancy, Finnigan was left to play a depth role. He did, however, chip in 20 penalty minutes. He didn’t score his first goal until 1925-26, when he he scored twice over 36 games while adding 24 penalty minutes.

The Last Senators’ Stanley Cup

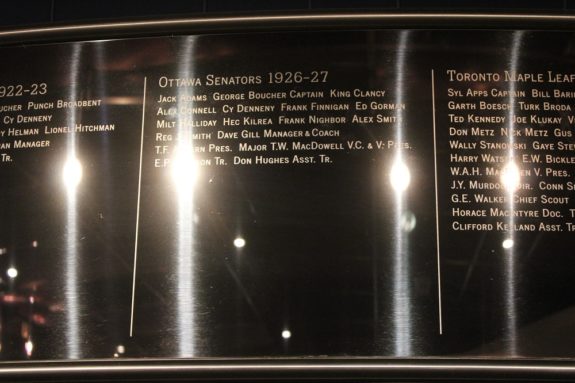

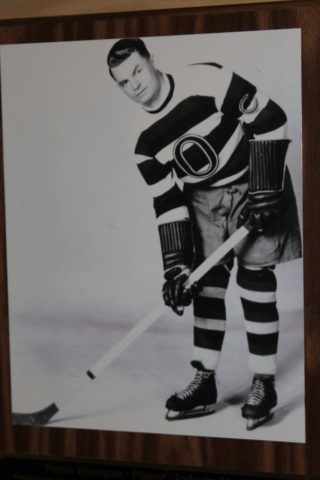

Finally, in 1926-27, Finnigan broke out. He scored 16 points, good for fourth in team scoring, and his 15 goals were only two behind Denneny. New goalie Alex Connell, who replaced Benedict, was even more spectacular, posting a 1.49 goals-against average and 13 shutouts. Along with talented newcomers Hec Kilrea and Reginald ‘Hooley’ Smith, the Senators captured their 11th Stanley Cup since their inception in 1883, the first time only NHL teams competed for the Cup.

Despite their success, the Senators struggled to be profitable. The market in Ottawa was just too small and the team was hemorrhaging funds. They eventually had to request financial help from the league. At first, the NHL allowed the team to play some home games in larger cities like nearby Detroit, but it wasn’t enough. The Senators were forced to sell any player with value just to make ends meet.

The first to go was Smith, who was traded to the Maroons for Broadbent and $22,500 in cash, just before the start of the 1927-28 season. Finnigan continued to grow into a talented sniper, leading the team in points (25) and goals (20) that season (followed closely by Kilrea’s 19 goals and 4 assists), but the team failed to advance past the quarter-finals. Then Denneny was sent to the Boston Bruins before the 1928-29 season and Boucher was traded to the Maroons mid-season for Joe Lamb. Although the Senators’ aging stars had only combined for six goals, their departure was felt throughout the organization. Finnigan led the team in scoring again, but with only 15 goals and 19 points.

The team’s fortunes changed in the 1929-30 season, when Finnigan and the Senators scored the most goals since joining the NHL. He scored a career-high 21 goals and 36 points, Kilrea led the team with 36 goals and 58 points and new arrival Lamb had 29 goals and 49 points, along with a team-high 119 penalty minutes. However, the Senators were upset in the quarter-finals by the New York Rangers.

Decline and Relocation

To start the 1930-31 season, Nighbor and Clancy were sold off to the Toronto Maple Leafs, the latter for $35,000 and two players, both of whom only lasted a single season in Ottawa. Unsurprisingly, the Senators sunk to last place for the first time since 1898 without their cornerstones. Finnigan also had an off year, scoring only nine times while adding eight assists. Kilrea hardly did better, with 14 goals and 8 assists.

Still, the Senators continued to lose money. In 1931-32, they suspended operations, loaning out their players in order to accumulate funds. Finnigan joined Clancy with the Leafs, where he regained some of his scoring touch with 8 goals and 13 assists, along with five points in seven playoff games en route to his second Stanley Cup. The Senators resumed operations in 1932-33 and Finnigan returned to the team along with Kilrea, Connell and growing star Syd Howe, but it didn’t help. Ottawa finished last again, and no one scored more than 27 points.

Connell and Kilrea were the last to leave, sold to the New York Americans and Maple Leafs, respectively, as the Senators desperately tried to generate income. Finnigan was the lone member of the 1927 Cup-winning team left on the roster. He bounced back in 1933-34 with 20 points and 10 goals, including the final goal in franchise history, but only tied for sixth in team scoring.

Related: The End of the Original Senators

He remained with the team when it relocated to St. Louis and played half a season as an Eagle, scoring just five goals and five assists, before the team sold him to Toronto. The Eagles folded after the season and Finnigan played until 1937.

Bring Back the Senators

After his retirement, Finnigan played for various amateur teams in the Ottawa area, including the Ottawa RCAF Flyers when he was a member of the air force during World War II. He returned to his hometown once he finished with hockey and, in 1953, opened a hotel in Shawville called ‘Finnigan’s’, which his son, Frank Finnigan Jr, helped run. It closed in 1980.

Finnigan remained an avid hockey fan, cheering on the Leafs. That is, until a group of potential owners approached him in 1989 about helping Ottawa gain another hockey team. The NHL had reconsidered plans to expand the league for the first time since the 1970s and, as the only surviving member of the original franchise, they wanted Finnigan to lend his support. He agreed, making several public appearances to generate interest and even helped give the initial presentation to the expansion committee.

The pitch was seen as a long-shot – if accepted, the City of Ottawa would be one of the smallest hockey markets in the NHL. Only Winnipeg and Quebec were smaller, and they had relocated in 1995 and 1996 to Phoenix, Arizona, and Denver, Colorado, respectively, due to financial struggles. Ottawa was also competing against 40 other hopeful cities, including Seattle, Halifax, and Saskatoon. Despite the odds, Ottawa was granted a franchise alongside Tampa Bay in 1990, with plans to begin operations in 1992-93.

Finnigan was told he would be the one to drop the ceremonial puck on opening night. However, when the day came on Oct. 8, 1992, it was Frank Jr. who was there; his father had died the year before. The team decided to retire Finnigan’s number despite the fact he’d never technically played a game for them. So, 55 years after he finished his playing career, and before the new Senators played their first game, Finnigan’s number was raised to the rafters.

Until Alfredsson retired in 2014, Finnigan was the only number retired by the Senators. It could be argued that no other player did more for the new franchise than Finnigan, who was instrumental in helping the team return to the NHL. He was never the biggest star, nor inducted into the Hall of Fame, but he helped bring the Senators back.