On the walls of a small house in Landrienne, Quebec, a tiny rural community in the Abitibi region 645 kilometers north of Montreal, hung three pictures: one of Pope Pius XII, one of Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis and the other of Maurice “The Rocket” Richard. These iconic personalities not only represented the main areas of popular interest and passion in 1950s Quebec, they also influenced the journey of those who grew up during this effervescent period of the province’s post-war history.

In this era, children typically grew up in an environment where politics and religion preoccupied adults while hockey fueled the dreams of young boys looking to imitate the exploits of their heroes. Gathered around a radio with his parents and three older siblings, Serge Savard listened attentively to the Montreal Canadiens games while dreaming of one day wearing the famed jersey on Montreal Forum ice that he and his friends worshiped.

In a much-anticipated biography, La Presse journalist Philippe Cantin colorfully describes the life and journey of the legendary Canadiens defenseman. In a compelling and highly insightful book entitled Serge Savard – Canadien jusqu’au bout (published in French by KO Éditions, translated title: Serge Savard – A Canadien till the end), Cantin shares Savard’s recollections of the most salient aspects of his unique hockey career.

Until now, Savard has been reluctant to share his life story. Cantin’s rigorous and thorough journalistic approach in weaving the biographical narrative creates an entertaining behind-the-scenes account of the key aspects of a hockey journey rich in dramatic, sometimes surprising, storylines both on and off the ice. Savard’s memoir is an appropriate pretext to rediscover some of the career highlights of one of the most colorful actors in the Canadiens’ rich history.

Early Career Success and a Lot of Pain

Savard’s father, Laurent, had a major impact on his children. Running a creamery out of the modest family home, he was also politically active, and became the mayor of their small town. Although the family valued and emphasized the importance of a good education, Laurent showed an open mind, uncharacteristic under the strict edicts of the time, when his youngest son asked for his approval to pursue his hockey dreams.

With his father’s blessing, Savard followed the required path. Similar to many hockey players looking to make their mark, Savard left the confines of the family home at an early age. He arrived in Montreal at the age of 15, and attended the Junior Canadiens training camp for the first time in 1961 as a center.

He made the team and played for the Junior Habs for three seasons, from 1963 to 1966. Others on the team also became household names, including Yvan Cournoyer, Jacques Lemaire, Rogie Vachon and coach Scotty Bowman.

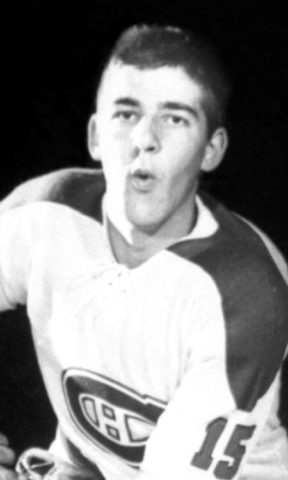

Savard’s skates first touched NHL ice in 1967, at age 20, when he played two games with the Canadiens. The following season, he continued his development with the Houston Apollos, a team within the Canadiens’ farm system. His NHL career officially started in the 1967-68 season, this time as a defenseman.

Success came quick. The team won the Stanley Cup in his first two seasons. He also became the first defenseman to win the Conn Smythe Trophy as the most valuable player during the 1969 Playoffs. His most ardent fans and supporters are proud to say that he won the award before Bobby Orr, a player he was often compared to.

Major injuries slowed his ascension to NHL notoriety. He broke his leg on March 11, 1970 in a game at the Forum against the New York Rangers. His leg was broken in five places and required three operations in the same week to repair. On Jan. 30, 1971, following a low hit by Bobby Baun of the Toronto Maple Leafs, Savard’s leg broke a second time and kept him out of action for close to a year.

Undefeated in the Summit Series

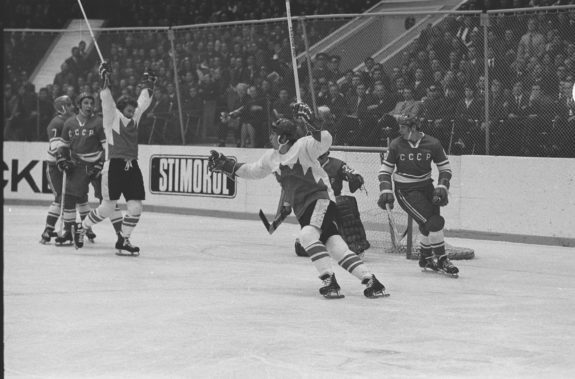

Playing in only 26 regular season and six playoff games in the 1971-72 season, Savard was not at the top of Harry Sinden’s mind as he prepared the list of players to be invited to try out for Team Canada ahead of what would be called the Summit Series. It was the first time, the best players from Canada played a team from the Soviet Union. Luckily for Savard, his former teammate and close friend John Ferguson was also part of the coaching staff and suggested Savard to Sinden.

Much has been written about this historic tournament that was held in the midst of the Cold War. For Savard, “it was the most difficult training camp I ever participated in.” He was a healthy scratch for the opening game of the series in Montreal. Following the shocking loss, Sinden tweaked the roster, allowing Savard to make his series debut in the second game and to play in the third. However, Savard was injured, again, when he took a shot by Red Berenson off his right ankle during practice that caused him to miss the fourth and fifth games of the series.

We had never played together and had learned to hate these guys. Bobby Clarke, Phil Esposito, not guys we would go out and have coffee with.

Serge Savard’s comments on his temporary teammates during the 1972 Summit Series. (Radio-Canada interview on Oct. 8, 2019)

With Team Canada trailing the series, Savard participated in the last three must-win heart-stopping games which led to Paul Henderson’s iconic goal that gave Canada the series win. In the end, Team Canada was undefeated in every game in which Savard played. In an interview with Radio-Canada leading up to his book launch, he acknowledged that participating in the Summit Series was the greatest experience of his career.

More Stanley Cups

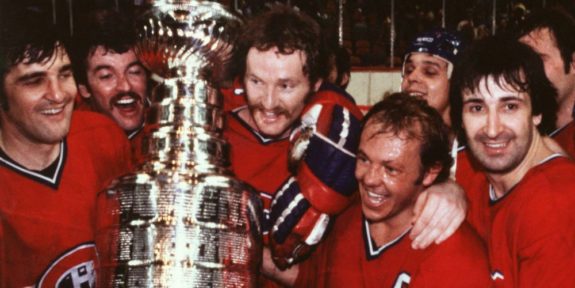

Following the euphoria of protecting Canada’s world hockey supremacy, Savard helped the Canadiens recapture the Stanley Cup in 1973. The Habs and the Boston Bruins had won the Cup in alternating years since 1970.

The arrival of Larry Robinson during the 1972-73 season completed what would be known as the Big Three. Along with Savard and Guy Lapointe, this trio of defensemen could help the Canadiens dominate the NHL for the final seasons of the decade. However, another team wanted to set its own mark.

As the game became increasingly violent, the Philadelphia Flyers’ brand of hockey, relying on intimidation tactics and aggressive play, led to two Stanley Cup Championships in 1974 and 1975. Savard was outspoken about what violence was doing to hockey, and when the Canadiens defeated the Flyers in the 1976 Stanley Cup Final, Savard called it “the most satisfying Cup I have won.” More Stanley Cups followed, with three more wins in 1977, 1978 and 1979.

Not Done Yet

Following the Canadiens’ elimination by the Edmonton Oilers in the first round of the 1981 Playoffs, Savard knew he had played his last game for the Canadiens. He was the oldest player on a team that needed to reset. He emotionally announced his retirement on Aug. 12, 1981.

However, during the following season, Ferguson again found Savard an opportunity. At the time, Ferguson was general manager of the Winnipeg Jets and following an embarrassing 15-2 loss to the Minnesota North Stars, he called Savard in the middle of the night. “I need your help,” Ferguson pleaded with his former teammate. “You could bring some order to our team.” Savard played for the Jets during the 1981-82 and 1982-83 seasons and was hoping to return for a third since his family enjoyed life in Winnipeg.

At the end of Savard’s second season, the Jets were eliminated by the Oilers in the first round of the playoffs. In the hand-shake line, Glen Sather, general manager of the Oilers said to him, “Serge, you’ll enjoy being GM in Montreal.”

At the time, Ronald Corey was president of the Canadiens and as a result of the team’s poor performance, he made sweeping changes to the front office staff. Rumours and speculation about who would be the next GM dominated the sports media in the city.

In my mind I had as much a chance of becoming GM of the Canadiens as I had of becoming the Pope.

Savard’s comment on his state of mind amidst rumors of his upcoming nomination.

When Savard realized that he might actually have a chance to be nominated, reality set in. “I wondered if I could do this job,” Savard remembers thinking. He also started to worry about comparisons that would be made to Sam Pollock, the legendary Canadiens general manager of the 1960s and 1970s who had saintly status in Montreal. Savard’s trademark calm and confident demeanor would be tested with this new career challenge.

Transition to the Front Office

Savard always regretted not pursuing his education when he was younger. The sacrifices made to to fulfill his hockey dreams kept him away from a formal classroom. Ironically, the lessons and relationships he developed as a professional hockey player would serve him better in the role he was about to take on.

On April 28, 1983, Savard, at age 37, became the first French-speaking general manager since the 1930s. The context under which he took over the team was daunting. Cantin writes that Savard could benefit from his status as a young retired player, but it also had the potential to create difficulties and uncomfortable situations. Some of the players he was now leading had recently been his teammates. He was now their boss. Savard had to shift his method of managing these relationships.

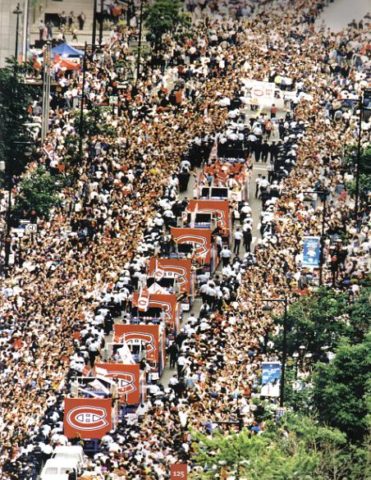

Similar to his career path as a player, success came early. In 1986, after a slow start to the season under head coach Jean Perron, the Canadiens unexpectedly won the Stanley Cup. Then in 1993, after defeating the Nordiques, Buffalo Sabres and New York Islanders, the Canadiens beat Wayne Gretzky and the Los Angeles Kings in the Cup Final to win the team’s 24th Stanley Cup.

A Bitter Ending

The euphoria of Savard’s second Stanley Cup as a general manger was followed by challenging seasons. They were eliminated in the first round of the playoffs in 1994 then missed them altogether in the following lock-out shortened season (1994-95). Corey put Savard on notice that things had to change. Cantin mentions a lengthy note that was given to Savard by Corey, essentially outlining the performance improvements he expected both of the team and of Savard’s workstyle.

After the Canadiens lost the first four games of the 1995-96 season, Corey acted. He fired Savard and head coach Jacques Demers on Oct. 17, 1995. It was a bitter pill to swallow for the proud Savard who felt that the team had the right players to succeed again. It was the end of a 30-year relationship with the team.

He was shunned by the organization after that, only returning to the Forum five months later for the last game at Montreal’s hockey shrine. However, the hockey community still recognized Savard’s contributions to the game by inducting him into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1986. It took 20 years for the Canadiens to offer similar recognition when the team retired his No. 18 jersey on Nov. 18, 2006.

Always Thought of as a Player

In retirement, Savard immersed himself in his many interests. Real estate, the stock market and race horses occupied his time along with the many charitable organizations.

The team relied on Savard in 2012 when the team’s owner Geoff Molson asked him to assist them in the search for a new general manager, that led to the appointment of Marc Bergevin.

Savard’s career was multifaceted. He was successful on the ice because of his hockey skills, size and determination. His success off the ice at the team’s helm was, in part, due to his ability to interact effectively with people, a trait he inherited from his father. In the final pages of the book, Cantin shares key insights into Savard’s view of his time in the front office of the Canadiens. “I had an asset, I kept the mentality of a player during all my years in office that helped me to go through many crises and the guys knew that I was there to protect them.”

There is a sense that Savard is still hurt by the way his association with the team ended in 1995. “I felt betrayed,” he says of the darkest episode of his illustrious career. His confident attitude, nevertheless, enables him to claim that he is still the last general manager to lead the team to a Stanley Cup over a quarter century ago.

Brief Notes on Savard’s Career

- First NHL game: Jan. 8, 1967

- First NHL goal: Oct. 21, 1967 against the Boston Bruins in a 4-2 win

- Conn Smyth Trophy winner: 1969

- Stanley Cup wins (as a player): 1968, 1969, 1971, 1973, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979

- Becomes captain of the Canadiens: March 12, 1979 on an interim basis while Yvan Cournoyer is injured (permanently in October 1979)

- Plays in his last game as a Canadien: April 9, 1981

- Played for the Winnipeg Jets: 1981-82, 1982-83

- Becomes General Manager of the Canadiens: April 28, 1983

- Stanley Cup wins (as a GM): 1986, 1993

- Fired as General Manager of the Canadiens: Oct. 17, 1995

- Inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame: 1986

- No. 18 jersey retired by the Montreal Canadiens: Nov. 18, 2006