The Buffalo Sabres made it to the Stanley Cup Final in only their fifth year of existence. When it came to Buffalo’s goaltending in those early years of the franchise, much of the duties fell upon the shoulders of the great Roger Crozier. Enough so that Sabres fans often forget the other goaltenders who helped backstop the team during that time.

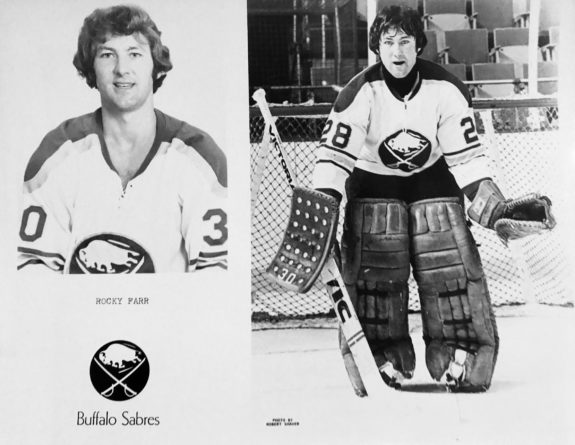

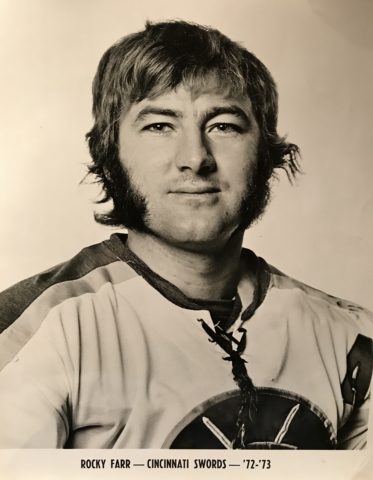

Within those first five seasons of play there were a total of six different goaltenders to go between the pipes for Buffalo. One of them was Norm “Rocky” Farr.

THW had a wonderful opportunity to speak with Farr one-on-one, nearly 45 years after his last NHL game. He shared stories with us that will not only be meaningful to Sabres fans, but that can speak to any fan of the game including some of his former teammates.

While his NHL career may have been brief, Farr still accomplished much at the professional level. We hope that you will appreciate his memories of those early Sabres teams as much as we did.

Overview of Farr’s Time as a Sabre

Looking at those same first five Sabres seasons, Crozier made appearances in each of them. Dave Dryden was second most, suiting up for games beginning with the inaugural 1970-71 season up through the 1973-74 – the latter of which saw Dryden acquire the bulk of the netminding duties for Buffalo.

Quite surprisingly though, it was Farr who played in the next most amount of seasons of the six goalies the Sabres called upon. After Buffalo selected him from Montreal with the 38th pick of the 1970 NHL Expansion Draft, he would only end up playing in 19 games as a Sabre. However, Farr’s playing time with Buffalo included appearances in the 1972-73, 1973-74 and 1974-75 seasons.

NHL expansion provided job opportunities to players who likely would have not cracked a roster prior to “The Great Expansion” of 1967.

Farr was born on Apr. 7, 1947 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Like most Torontonians, he dreamed of playing in the National Hockey League since a very young age. It was NHL expansion and the Buffalo Sabres that would enable Farr to see his dreams become reality.

First things first though – we needed to find out how Norman Richard Farr stemmed into the better known moniker of “Rocky” Farr.

How He Got the Name “Rocky”

Nicknames for hockey players seem to come more naturally and more readily the further one goes back into the annals of the game. Hockey lore has given us numerous colorful names including Fred “Cyclone” Taylor, “Phantom Joe” Malone, and “Newsy” Lalonde. Fast-forward to the 1970s, and the list of Farr’s contemporaries includes nicknames such as “The Flower”, “The Pocket Rocket”, “The Hammer”, “Moose”, “Big Bird” and many more.

So how did Norm Farr gain the better known name of “Rocky”? Oddly enough, the name was bestowed upon him by one of hockey’s greatest innovators.

“Roger Neilson,” Farr stated.

The 2002 Hockey Hall of Fame inductee was perhaps best known for his hockey innovations of using videotape to analyze other teams. This helped earn Neilson his own nickname, “Captain Video”. Neilson was also the first to employ the use of microphone headsets so that he could communicate with his assistant coaches. He coached eight different NHL teams during his career, but in the 1960s Neilson coached Farr and other youngsters in two different sports.

“I played baseball and hockey for him,” Farr went on to say, “starting at around nine or 10 years old. Roger needed a goalie. I was actually a forward, but he said I was a good athlete. He needed a goalie, so he said ‘I’ll show you how to play goal’.

Farr’s decision to become a goaltender for Neilson and learn from his mentor would be the beginning of the path to professional hockey. The nickname however, ended up coming from baseball.

“I wasn’t a very good hitter,” Farr explained. “Roger was working on my hitting, and he had me kind of turn sideways so I could see the ball better. Pete Rose kind of turned to one side too. Toronto had a baseball team in the International League called the Toronto Maple Leafs. They had a first baseman whose name was Rocky Nelson. Roger had me do the same stance as Rocky, he was a first baseman and left-handed. I was a right-handed hitter, but I was left-handed as far as playing first base. It just caught on when you’re that young with nicknames, so they just started calling me Rocky. That name has stuck with me since I was 10 years old.”

Neilson’s Mentorship

Roger Neilson gave Farr well more than just a nickname. He gave him the necessary tutelage of a coach, but was also very much a father figure to him as he was for many other young men.

“Roger was a great baseball coach,” Farr was able to explain. “For many of us whose fathers didn’t go to the games, he was our father. He picked us up and he took us to games. We went to Detroit several times and Cleveland to see the big league games. He took us for weekend trips. He was just like our dad. He was the most wonderful person in the world, and I was fortunate to be with him probably all the way up to age 15 for baseball and hockey.”

Nothing in life happens by coincidence, at least not when it comes to the important things. Neilson played an integral role in what would ultimately lead to an NHL career for Farr.

“My Midget year, when I was 15 years old, Roger was both my coach and a pro scout for the Montreal Canadiens, and Scotty Bowman was the Chief Scout for the Canadiens. He was probably the greatest NHL coach of all-time. He was so impressed by my playing that he wanted me to come to Montreal to be groomed for five years with the hope that I would be the next Jacques Plante. As history played out, this did not happen but the life lessons I learned by being on my own at such a young age paid off in my transition from the status of well-known hockey player to an average person.”

Farr played the majority of his junior hockey career in the Ontario Hockey Association. He played for the London Nationals, the precursor to today’s London Knights. In fact, he was the first goaltender in London’s OHA/OHL history. Farr also played for the Montreal Jr. Canadiens and the Oshawa Generals.

From Montreal’s Property to Buffalo’s

Back in the days of the “Original Six”, NHL teams would sign youth hockey players with the intent of grooming them up through junior hockey in their teenage years to eventually play professionally someday. It was a farm system approach that had the mindset of raising youth players that would eventually make a roster in the NHL. The problem was that with only six teams at the time, there were no guarantees that a player would make it onto the NHL.

For skaters it was bad enough. For goaltenders, it was even worse. And for goaltenders in the Canadiens’ system, it was arguably the toughest competition to make the roster in the 1960s out of any professional sport, period. Hall of Famers Jacques Plante, Gump Worsley, Tony Esposito, and Rogatien Vachon all spent time in the Montreal net during the decade. That is not even mentioning Charlie Hodge, Ernie Wakely, and Cesare Maniago who were also solid netminders that spent at least some time in the Canadiens’ net during the 1960s.

Farr would not see any NHL action durings the 1960s himself. He would play his first professional-level games with the AHL’s Cleveland Barons, the CHL’s (then CPHL) Houston Apollos and the WHL’s Denver Spurs as the decade came to a close.

After the NHL expanded to 12 teams for the 1967-68 season, they would follow it up by adding two more for the 1970-71 season. The Buffalo Sabres and the Vancouver Canucks would be added to the league as the NHL welcomed in the new decade.

The 1970 Expansion Draft was held on Jun. 10. The Sabres and the Canucks alternated between picks, with Buffalo picking first. As the draft moved along into its final stages, goaltenders would comprise the final four picks.

The Sabres would make Farr their first choice of the two goalies they selected, and he was taken from Montreal as the 38th pick overall. He was excited for the opportunity to play for his new club.

“I was elated because back then they only had six teams,” Farr remembered. “There was no way I had a chance to play in the National Hockey League without expansion, and that’s true for many, many players. At that time I just thought it was a great opportunity because that was always my dream, like pretty well every Canadian kid that always wants to play in the National Hockey League and be a professional hockey player. That was great, and I was excited that hopefully I’d get that opportunity to play.”

Playing for the Sabres

The Sabres had a bit of a logjam of their own in net during their first two seasons. With Crozier, Dryden, and the maskless Joe Daley manning the nets, Farr remained in the minors. He would spend the 1970-71 season with Buffalo’s WHL affiliate the Salt Lake Golden Eagles.

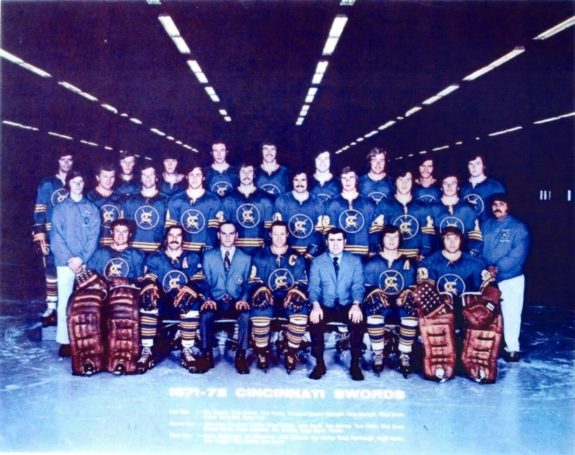

When the Buffalo Sabres exercised their option to create their own AHL affiliate, the fledgling Cincinnati Swords were formed beginning with the 1971-72 season. Farr became Cincinnati’s number-one goalie.

In the franchise’s second season – 1972-73 – Farr was fortunate enough to play on a veteran team which won the AHL’s Calder Cup that year, with Farr playing the majority of the games. What made that season extra special in particular was a conflicting arena commitment for the sixth game of the playoffs’ Final. The Cincinnati Gardens arena was not available, so the game was scheduled to be played in Buffalo’s Memorial Auditorium. Naturally, the whole team was excited to have the opportunity to play there with the Swords being the Sabres’ affiliate.

The game was played to a nearly sellout- crowd, with attendance from many of the team’s family members. Farr and the Swords won the Calder Cup that night. Along with the celebration of the win, the Sabres owners Seymour and Northrup Knox gave all the players $5,000 and championship rings.

Solid play for the Swords and Crozier’s long-term battle with pancreatitis would earn Farr, Buffalo’s third-stringer, his first NHL action.

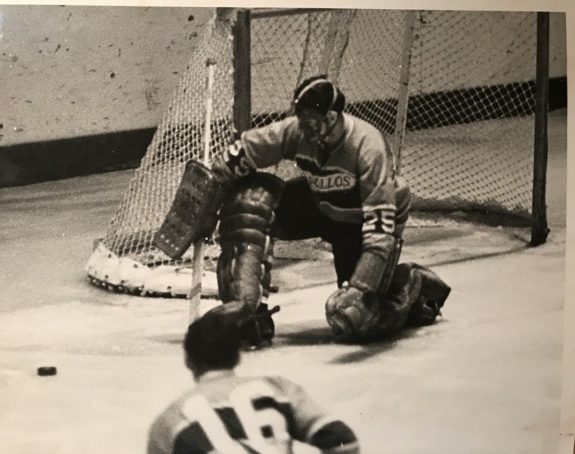

Farr would make his NHL debut on Jan. 4, 1973. The Sabres played the Red Wings at the Olympia in Detroit. Farr would earn the start against the Red Wings, and was perfect through the opening period. He would however be pulled in favor of Dryden after allowing three straight goals in the second period in a span of 8:47. Hockey Hall of Famer Alex Delvecchio netted Detroit’s third, and the Red Wings would go on to win 4-2.

While Farr did not recall much about his first NHL game, he did clearly remember how difficult it could be for a goalie to play at the Olympia. Nicknamed “The Old Red Barn”, it was not a friendly confine for an opposing goalie.

“I remember playing in Detroit,” Farr shared. “That old arena was like playing in a sandbox. It was a nightmare for a goalie. On a good slap-shot, they could probably score from center ice. It was really tough. I don’t know how Roger Crozier and Terry Sawchuk had such great careers there. I can tell you that for me, the corners were right beside you. It was hard – you always had to be on your toes wherever the puck was because it was such a small ice surface.”

Old Rinks and a Different Game

Farr’s entire 19-game NHL career was spent with the Sabres. Nine of those 19 were games that he started, and his final career record came to 2-6-3 across the three seasons that he played. That record includes a 3.50 goals-against average, and a .894 save-percentage which is a rather decent number for the 1970s.

19 might be the number in the official record books, but Farr also spent a considerable amount of time on the road with the team and on the bench. He recalled with a bit of incredulity what it was like being the backup in 1970s NHL rinks.

“I remember sitting on the bench many times,” almost shaking his head between then and now. “Back in those days when you sat on the bench the goalie just kind of sat on the far end of it, and the fans were sitting there right with you. We didn’t have any Plexiglas or anything, so you’re sitting there carrying on a conversation with the fans. In those days we had very few issues with the fans as far as heckling, though later on (that changed). A lot of rinks were that way. You were right there on the bench, and then they started changing it where you were separated from them.”

Management’s approach back then was quite different too. The Sabres’ General Manager in the first seasons of the team was the hard-nosed Punch Imlach. A Hockey Hall of Famer and a Stanley Cup-winning coach with the Toronto Maple Leafs during the 1960s, Imlach was tough and very much old-fashioned in terms of how he handled his players. He was even known to bag skate some of the early Sabres if he thought their hair was too long, as was told by former Sabres’ defenseman Doug Barrie in Ross Brewitt’s Sabres: 26 Seasons in Buffalo’s Memorial Auditorium.

Farr looks back on his approach to Imlach as possibly having been a mistake.

He stated:

“I don’t know if it would’ve changed much about my career as far as what I would’ve accomplished, but after the ’72-’73 Calder Cup championship I held out for a new contract and didn’t report to training camp until they signed me to a new two-year deal. Punch was the GM at the time. Back in those days you didn’t have an agent to negotiate your contract. Looking back, it was a mistake I made on my career because from that point on I really didn’t get the opportunity that I had hoped I would get. Unfortunately, back in those days management dictated what players earned. So players who made waves, unless they were a superstar, were more than likely at some point in their career to be spurned by management. I had some good years in Cincinnati, but it wasn’t as if the (Sabres) direly needed me. It was a perfect opportunity for them to not give me a chance to play.”

Memories of Buffalo

Farr’s longest stretch with the Sabres came during the 1973-74 season. Through 11 games he went 2-4-1 with a solid .905 SV%. He would earn his first NHL victory on Feb. 8, 1974 against the California Golden Seals. Farr and the Sabres took a decisive 7-2 victory as he turned aside 25 of the 27 shots that he faced. More than twice during the 11 games he was peppered for at least 40 shots too.

A decent enough performance on Farr’s behalf, but in addition to his contract dispute with Imlach he also had to outdo both goaltenders ahead of him in the depth chart. That in and of itself was by no means easy.

“During that time Dave Dryden and Roger Crozier were the two goalies,” Farr recalled about his teammates who were also his competition. “And both were excellent goalies. Dave Dryden played a lot when Roger couldn’t. The times that I was up there, it would have been difficult to beat out Dave anyway. I don’t know if being a better goalie than Dave, I may have been able to compete with him. Those two goalies did a great job for the Sabres during those years.”

Tim Horton

Some of Farr’s fondest memories from his time with the Sabres are those of the legendary Tim Horton. As did all of the Sabres – especially the younger ones – they looked upon the late Hall of Fame defenseman with the sincerest respect and admiration. Horton played only two seasons in Buffalo, but the impact he made upon his teammates and the franchise has lasted a lifetime for everyone. Enough so that his number-2 jersey has been retired by the Sabres since 1996.

“Probably I would say the person I was closest to was Tim Horton when I was there,” Farr recalled fondly. “He took all of the new players under his wing. He took care of them, and you stayed with him. He made sure that everything was okay. Of all the hockey players that I’ve ever met, he was just down to earth. He would do anything – he was a team player. Tim Horton was the person who impressed me more than anybody else.”

Horton was tragically killed in an automobile accident in the early morning of Feb. 21, 1974, as he drove home alone from Toronto to Buffalo. Horton and the Sabres had just played the Maple Leafs hours prior. Even though the Sabres had lost that game, Horton earned one of the Three Stars of the Game despite having played with a broken jaw and an ankle injury.

As fate would have it, Farr was in net for Buffalo in the game against the Leafs which would be Horton’s last. He would then suit up again less than 24-hours later for Buffalo’s home game against the Atlanta Flames the same day of Horton’s death. Farr and his teammates wore black armbands for the game against the Flames, with many of the players openly crying on the ice prior to puck-drop.

Understandably, it was a highly emotional experience that still resonates with Farr to this day.

“The memory I’ll never forget,” he said with a touch of emotion even all these years later, “was the night I got the phone call at 2 o’clock or 3 o’clock in the morning to tell us that we had to be at the rink earlier in Buffalo because Tim had gotten killed while driving home. I actually played that game in Toronto when he got killed on that night. I remember that we wore the black armbands for the next game, and I played that game too. We played Atlanta, and we tied 4-4. That was one game, one period of time that I’ll never forget, especially because we all loved Tim. I wasn’t the only one who respected him, but just thought that he was the greatest person in the world – all the others did too. He was the biggest link to the success of the team. He played for the Leafs and had such a great career. He was 44 years old at that time, but he had a body on him like a 24-year-old. He was in great shape. Built really stocky.”

Tumultuous…

Farr would play one final season for the Sabres – 1974-75 – as they made their run at the Stanley Cup. He was one of four goaltenders who saw action that season, with Crozier, Gary Bromley and Gerry Desjardins being the others. While it was exciting times for the city of Buffalo and the Sabres themselves, it was more of a tumultuous time for Farr.

He would play in just seven games that season even though he spent the entire season in Buffalo. In that time his record amounted to 0-1-2. What further added insult to injury was that the Sabres had acquired Desjardins late in the season when they made a trade with the New York Islanders on Feb. 19, 1975. Desjardins was very much considered a starting goalie in his own right, and the Islanders were willing to part with him due to the emergence of Billy Smith and Glenn “Chico” Resch on Long Island. However, the move only pushed Farr further to the wayside amid his own trying relationship with Imlach.

“It was turbulent times really for me,” he shared with honesty but no bitterness. “As a player, you want to play more. It’s the old thing where when you’re not playing you’re not really happy about it. That part of it, and knowing the issue of why I wasn’t getting the opportunity really bothered me a lot.”

After the 1974-75 season came to a conclusion, the Sabres traded Farr to the Kansas City Scouts on Oct. 1, 1975. At this point though, he was done playing in the NHL and never suited up with the Scouts. Farr played his last season (1975-76) with short stints with the Springfield Indians of the AHL and the Johnstown Jets of the North American Hockey League (NAHL).

And Fondness

Farr is a gentleman, and does not hold any grudges as to how things ended in Buffalo. When the Sabres held their 40th Anniversary celebration, he took part in the festivities and was welcomed out onto the ice with the many other players who comprised the team during the 1970s.

Though he is now in his early-70s, Farr still has great things to say about his time in Buffalo. He particularly recalls the affinity he had for the two coaches he played for as a Sabre and a Sword.

“Joe Crozier. He was another type of mentor-coach and well-respected. I enjoyed playing for him. Floyd Smith was another one that I enjoyed playing for. He was one of the coaches who kind of let the players coach themselves. A players coach. He was our coach when we won the Cup in Cincinnati that year. And he had a great career with the Toronto Maple Leafs as a player.”

Farr could also never forget how great Buffalonians are and how much they love their team. Additionally, he recognizes that it was a real treat for him to suit up with one of the greatest forward lines in hockey history.

“The fans were great,” Farr said most fondly. “It was a great place to play hockey. I think if anything – as far as where you could play – I think Buffalo was a great place to play. The Knox brothers who were the original owners of the team, they were super to all the players. The fans treated us very well. I enjoyed playing in The Aud. Fortunately I got to play with Gilbert Perreault. The French Connection line to me through history is so tough to beat. Richard Martin, Rene Robert, and Gil Perreault – they were a super line. Finesse and entertainment, they were great. I had a chance to practice against Gil Perreault all the time, and see the great moves he had. He was an unbelievable hockey player. He was like Bobby Orr – just very talented and a natural athlete.”

Hockey Taught Farr Life Skills

Rocky Farr and his wife Susan of 25 years live in Fort Worth, Texas. Farr is a Partner and Vice President of the Diesslin Group, Inc., a financial advisory and wealth management firm in Fort Worth.

The Farrs routinely commute to London, Ontario and Toronto to visit with family. With Farr having made hockey history by being the first goalie in the London Jr. A franchise, he and his wife have set up a hockey fund through the London Knights/Jr. A Nationals Alumni Foundation. Its mission is to help special needs children or children of families who may otherwise struggle to make financial ends meet be able to participate in some type of hockey program. The fund is Farr’s way to give back to the game that has given him so much and to keep involved with hockey in some capacity.

Furthermore, Farr recognizes that hockey has given him life skills – one being the understanding that to be successful in life you must learn to be a team player. As a goalie, you must rely on those other five players who are with you on the ice. What success a goalie may have is dependent upon how everyone works as a team. This stems from Farr’s youth as one of Roger Neilson’s kids up to now, some 60 years later.

“I feel so fortunate to have played in the NHL since it was such a wonderful experience and a dream come true!”